The real trouble with Kneecap

The perils of the single transferable victim

Kneecap aren’t the sort to go meekly to court. So when Mo Chara turned up at Westminster Magistrates this week, neatly arriving a few days before the group’s Glastonbury performance, his appearance was heralded by an actual advertising campaign.

In fact, an advertising campaign that came with its own advertising campaign, with shaky handheld camera footage showing astonished onlookers taking photos with their mobile phones of billboards emblazoned with the slogan: “More Blacks, More Irish, Mo Chara”.

The “provocative” projection and billboard campaign was put together by an advertising agency founded by the guy responsible for Paddy Power’s marketing gimmicks that works for giants like Primark, Guinness and Maserati.

The creatives of course put it in loftier terms. The “More Blacks…” slogan was about “reclaiming the language of historic exclusion as a message of solidarity, resistance, and cultural pride”.

In style and in substance the campaign says everything about Kneecap, a group so desperate for victimhood that they’ve travelled, mentally, halfway around the world for the purpose.

The slogan is a retelling of the infamous “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs” notices that were affixed to boarding house windows in postwar Britain. The only snag is that the scant evidence these notices existed.

You only need to scratch the surface of the newspaper archives to see mid-19th century job ads marked “No Irish Need Need Apply” and, as the century wore on, angry letters decrying them.

But “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs”? The genealogy is peculiar. The earliest reference I can find in the archives is 1987 in the News Letter, where a group advocating for the rights of homeless Irish in London refers to a “mentality” that was described as “still rife”.

The explosion of this particular phrase gets to the heart of the Kneecap schtick: an odyssey to find victimhood of a higher grade, a purer hit. Like a junkie staggering to ever harder substances, they’ll borrow from the past, from the United States, from Gaza.

The Northern Ireland Kneecap were born into had no shortage of bigotry, but the in-built sectarianism of the old Stormont regime – gerrymandering in Derry, a property requirement for voting in local elections, no protection against discrimination in the job market – had been dismantled in the days of their grandparents.

On the Kneecap website you can buy a £25 “RUC not welcome tee”, in reference to a police force that was reformed and renamed before Mo Chara was in primary school.

Die-hard republicans had as much difficulty accepting the new Police Service of Northern Ireland, with its mandatory Catholic recruitment, as the IRA did in accepting the old RUC. And so, just like the IRA, they took special care to target the Catholics in the service.

Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Agreement simply doesn’t create the grievances Kneecap yearned for, especially once the Irish language won official status and the DUP were knocked from their perch as the largest party.

Gaza and the US race relations offer the allure of moral clarity. A sort of single transferable victimhood.

Let’s go back to the start.

Kneecap’s stylish and funny movie – think Hard Day’s Night with drugs and balaclavas – kicks off with a voice-over explaining the idea of Penal Law-era mass rocks to a global audience, where “just a few generations ago” Irish Catholics went “to practise their own religion and speak their own language”.

“A few generations ago” is doing so much work here that it should unionise and hire someone from Paddy Power to highlight its plight with a guerrilla marketing campaign.

The Roman Catholic Relief Act granting freedom of worship was in 1791. And the Irish language was never banned. (Though penal laws did establish English as the official language of the courts and the National Schools introduced in Ireland from the 1830s onwards taught in English).

In another important moment, Mo Chara’s future bandmate’s dad, an IRA man played by Michael Fassbender, encourages them to watch the Western on the TV from the Indians’ perspective: “Cowboys are cunts”. It is an echo of James Baldwin’s immortal line on black alienation in the America of his youth: “that it comes as a great shock… that the Indians are you.”

Kneecap are part of a broader revisionist trend to distort the Troubles into a struggle for rights between downtrodden indigenes and colonial overlords, rather than a murderous, sectarian attempt to wrench Northern Ireland from the UK and a murderous, sectarian attempt to stop it. The cowboys-and-Indian settler-colonial model falls woefully short when it comes to Northern Ireland.

Inevitably, Gerry Adams, fresh from his BBC libel victory, used his X account to amplify the “More Irish, More Blacks” campaign. A more humble politician would have put his social media permanently beyond use nine years ago when he used the n-word after seeing Django Unchained – and for an apology likened the treatment of Catholics in 1960s Northern Ireland to slavery and segregation in the American south.

Pre-Troubles Northern Ireland was famously described as a “cold house for Catholics” by David Trimble, the late Nobel-winning unionist leader. But it’s borderline offensive to compare it to the Jim Crow or antebellum south.

Adams and other republicans vicariously claim the mantle of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association – a mantle that belongs to the moderate nationalist SDLP if it belongs to any party – in order to justify a prolonged, murderous campaign that ultimately settled for a political accommodation that republicans rejected in the early 1970s.

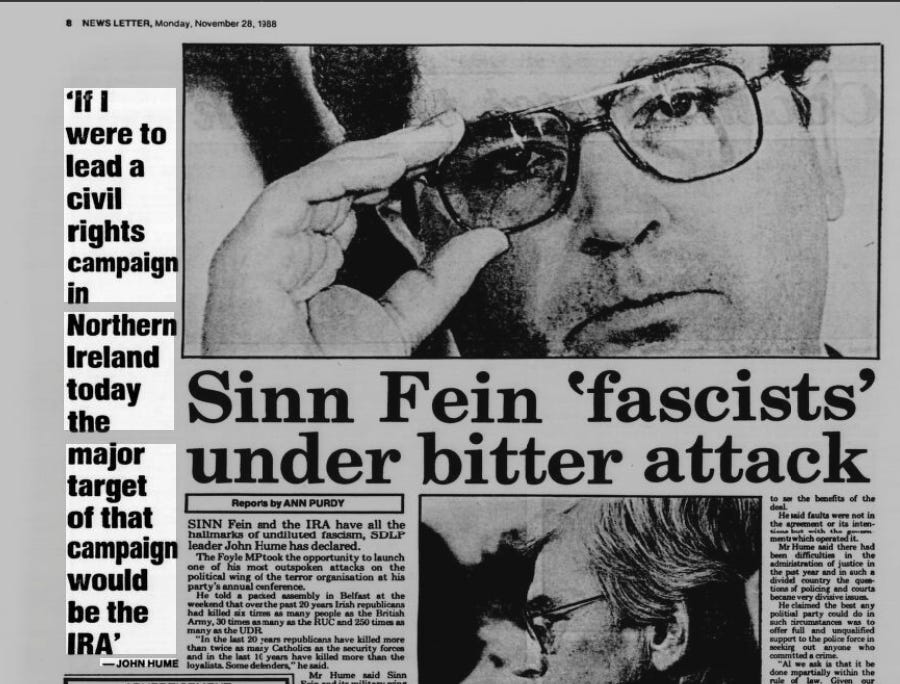

By the 1980s, John Hume, the Nobel-winning nationalist leader, was arguing that the biggest impediment to civil rights in Northern Ireland was the IRA.

Killing on the scale of the Troubles was only possible because of deep-seated cultures of grievance and victimhood among both loyalist and republican communities. If the price of liberty is eternal vigilance, maybe the price of peace is historical pedantry.

This is the real shame about Mo Chara’s prosecution. By dragging him to court for something he allegedly said – however reckless, however cruel – he at last has what he always wanted: something to complain about.

And victimhood, as everyone from Northern Ireland knows, is a dangerous thing.